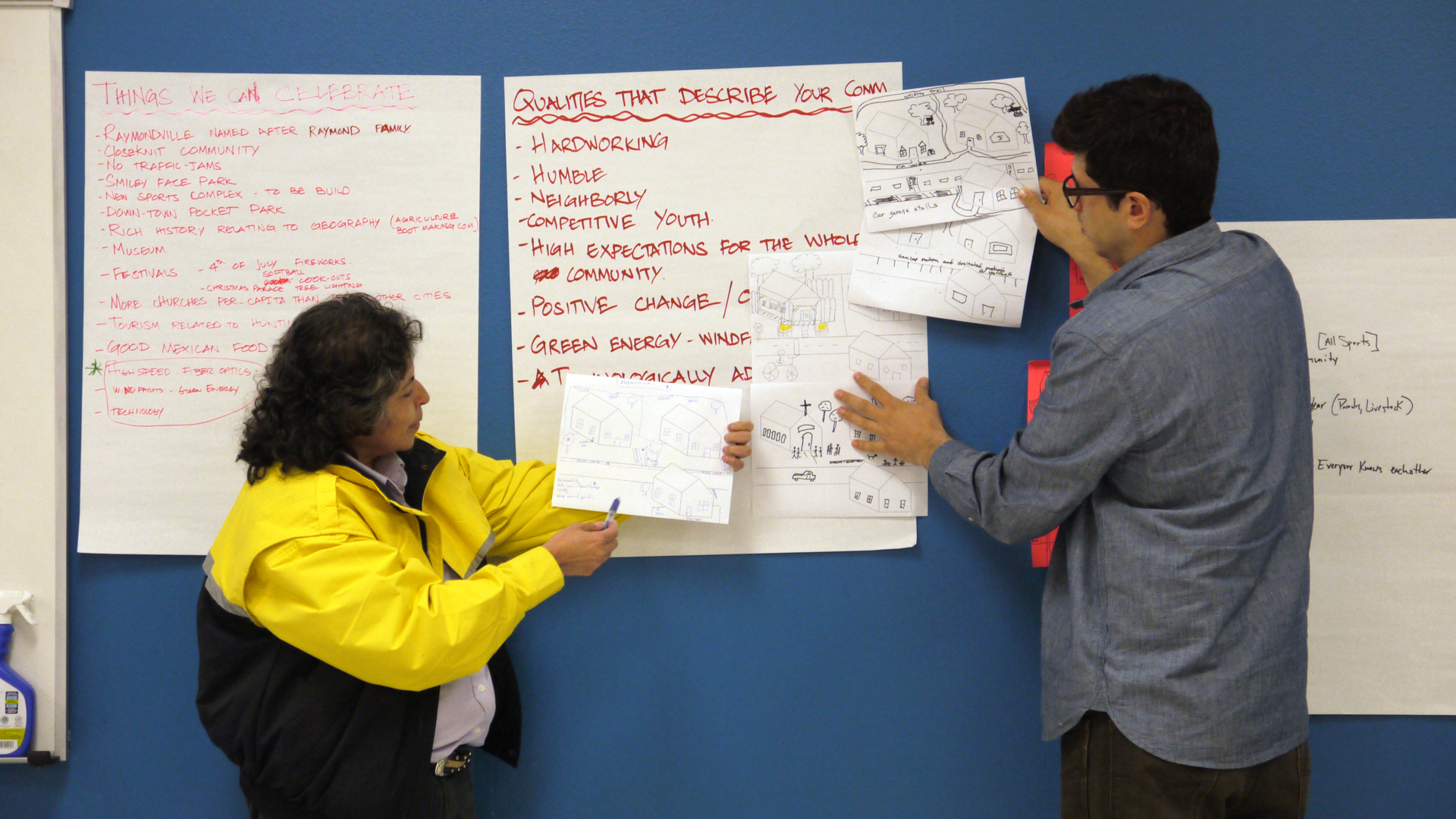

Race and the Control of Public Parks is a 100 year history of the relationship between racial migrations in Dallas and the development of the city’s park system. An exhibit of graphical and historical research, Race and the Control of Public Parks makes evident that while parks are technically public and that all citizens are, in theory, automatically welcome, we must recognize the ways in which the design, construction, programming, use, and alteration/renovation of public parks can reinforce divisions, both physical and perceived, between populations. Launched on November 14 to coincide with the Facing Race Conference, a national assembly tackling racial justice, this project is just one component of an important critical conversation about racial inequity in cities.

To provide a comprehensive understanding of how the racial makeup of the city has shaped the design and use of public space, the exhibition was composed of four parts: a series of ten historic maps and one contemporary map that trace residential patterns by race and the parks system; an annotated timeline of the evolution of Dallas parks and park typologies over the last 100 years; a series of diagrams that illustrate parks as tools for or sites of nine types of social, economic, infrastructural, and civic controls; and a series of snapshots that illustrate the impact of these controls as they relate specifically to parks and race in the city of Dallas.

This exhibit provides the tools to interrogate the physical city and reveal the multiple ways in which we plan, build, and interact with it, exercising these tools through the lens of public parks and race. As a result of this work, parks will no longer be viewed simply as the green spaces on the map but will be recognized as places of recreation, conflict, celebration, engagement, protest, and daily life. Public parks will be seen as tools used to control social, cultural, economic, infrastructural, and civic activities.

Research and work produced for this exhibit lay the groundwork for extended work around the Control of Public Space, which will move beyond parks and look at sidewalks, streets, easements, and other forms of public space in the city. This work, like many People Organizing Place projects, gives citizens the ability to experience the city around them with new awareness, revealing hidden voices, histories, and controls that impact their lives on a daily basis. As citizens, we must work to understand our cities and to make them more livable and just for all, especially in our most public places, parks.

What others are saying:

![[bc]](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5248ebd5e4b0240948a6ceff/1412268209242-TTW0GOFNZPDW9PV7QFXD/bcW_square+big.jpg?format=1000w)

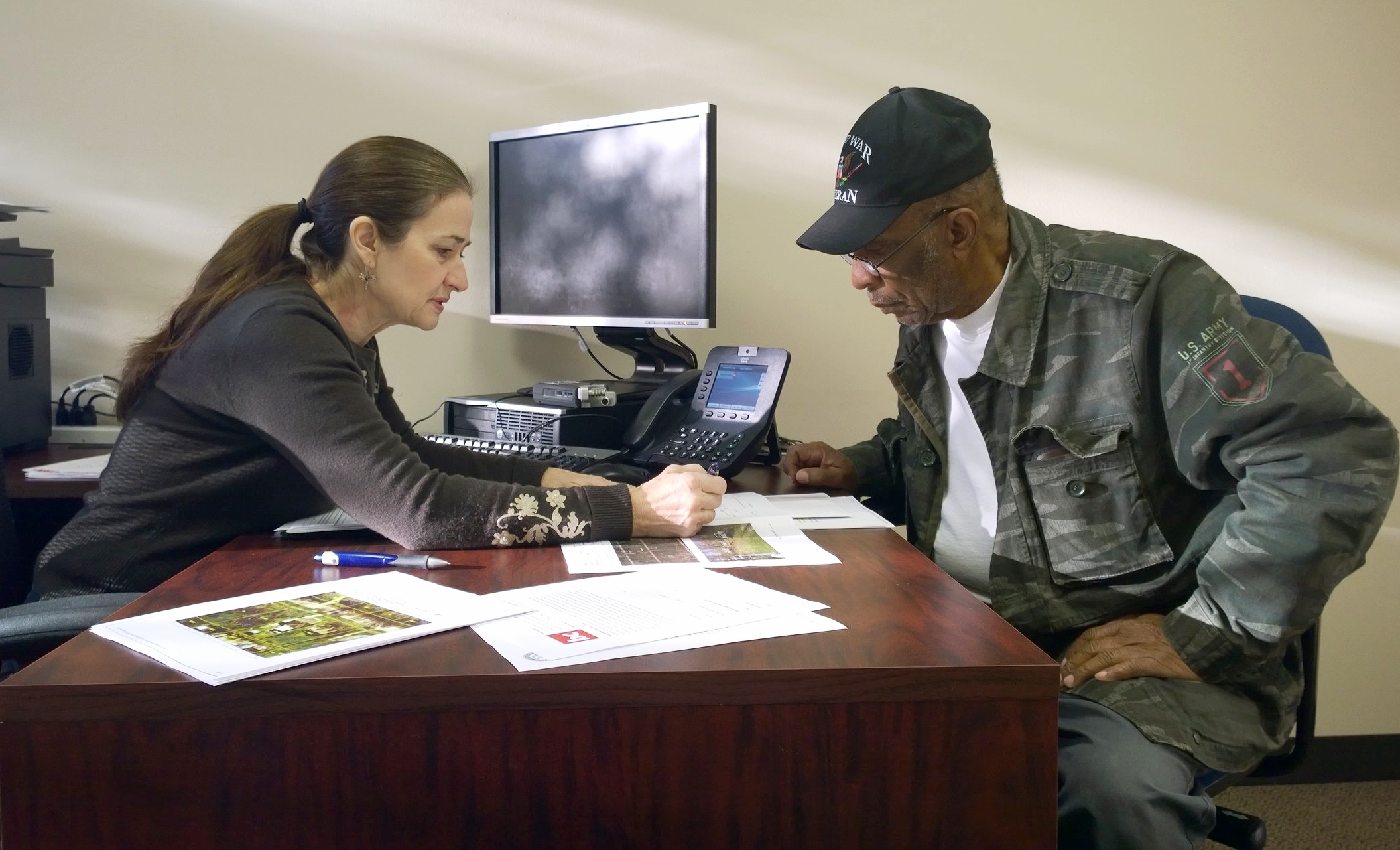

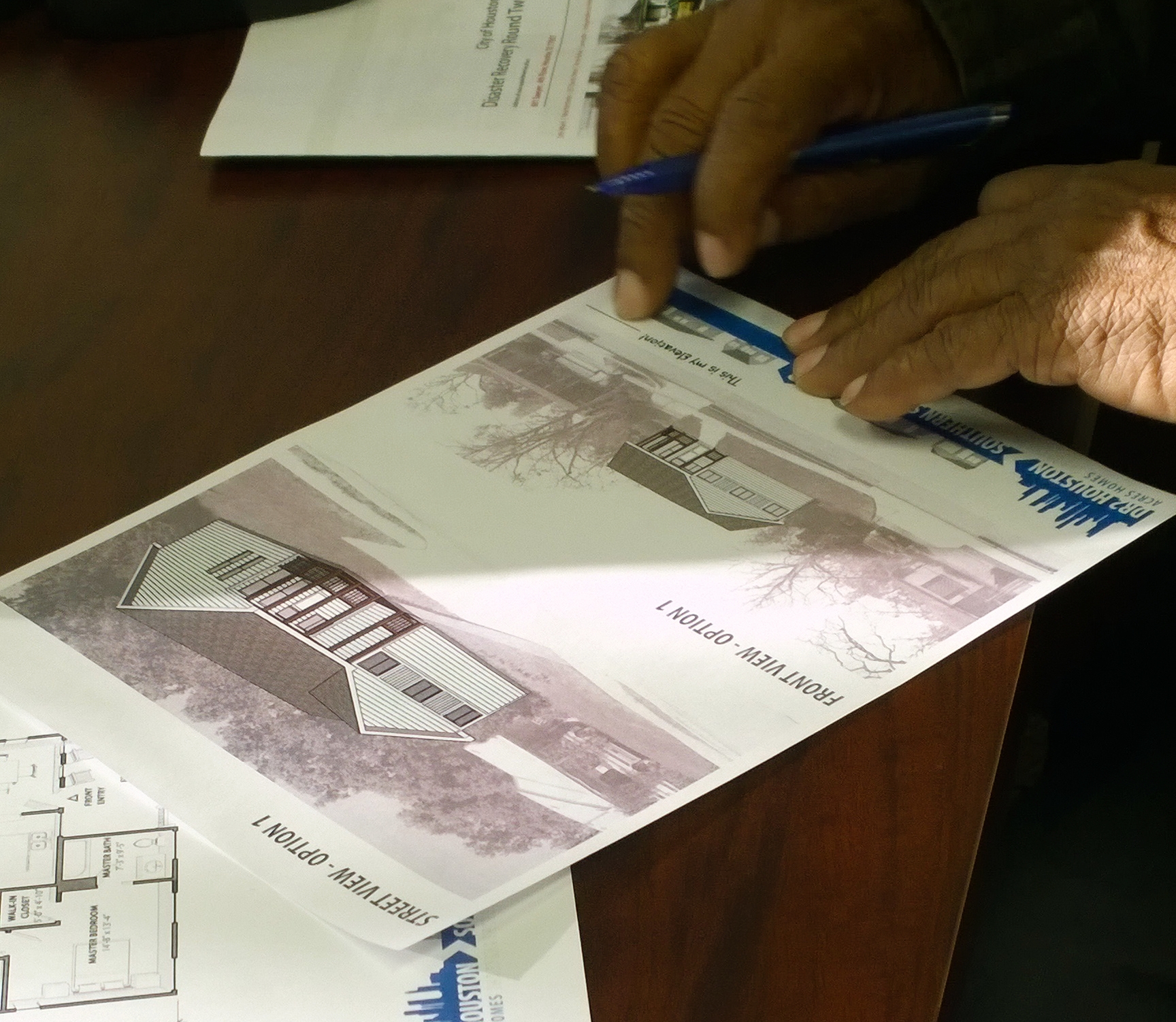

![[bc] Planning Associate Lisa Neergaard assess the inside of a RAPIDO pilot home.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5248ebd5e4b0240948a6ceff/1424298105612-9INKNYU0O3Y8XWM8PVUH/P1000888.JPG)

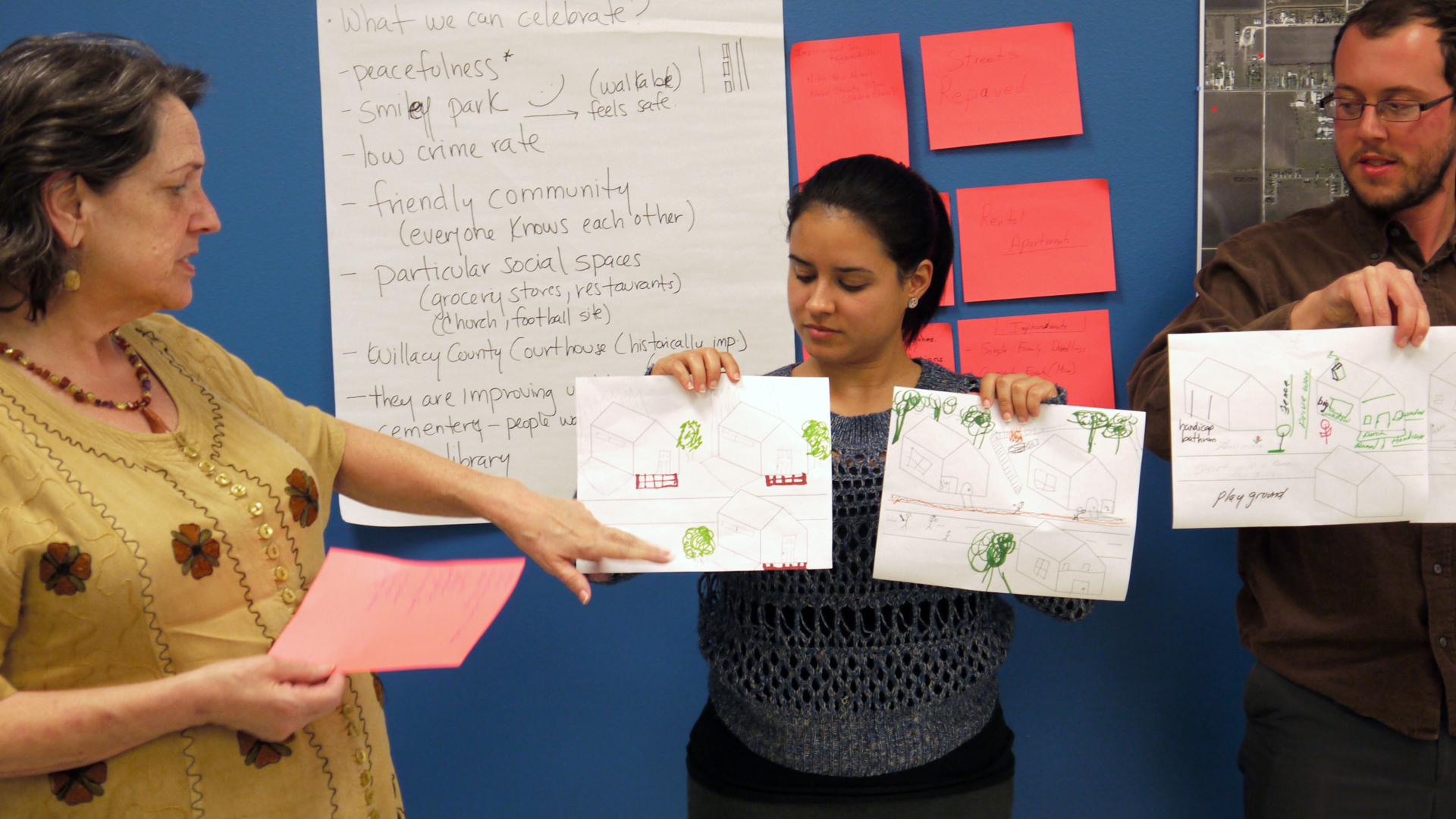

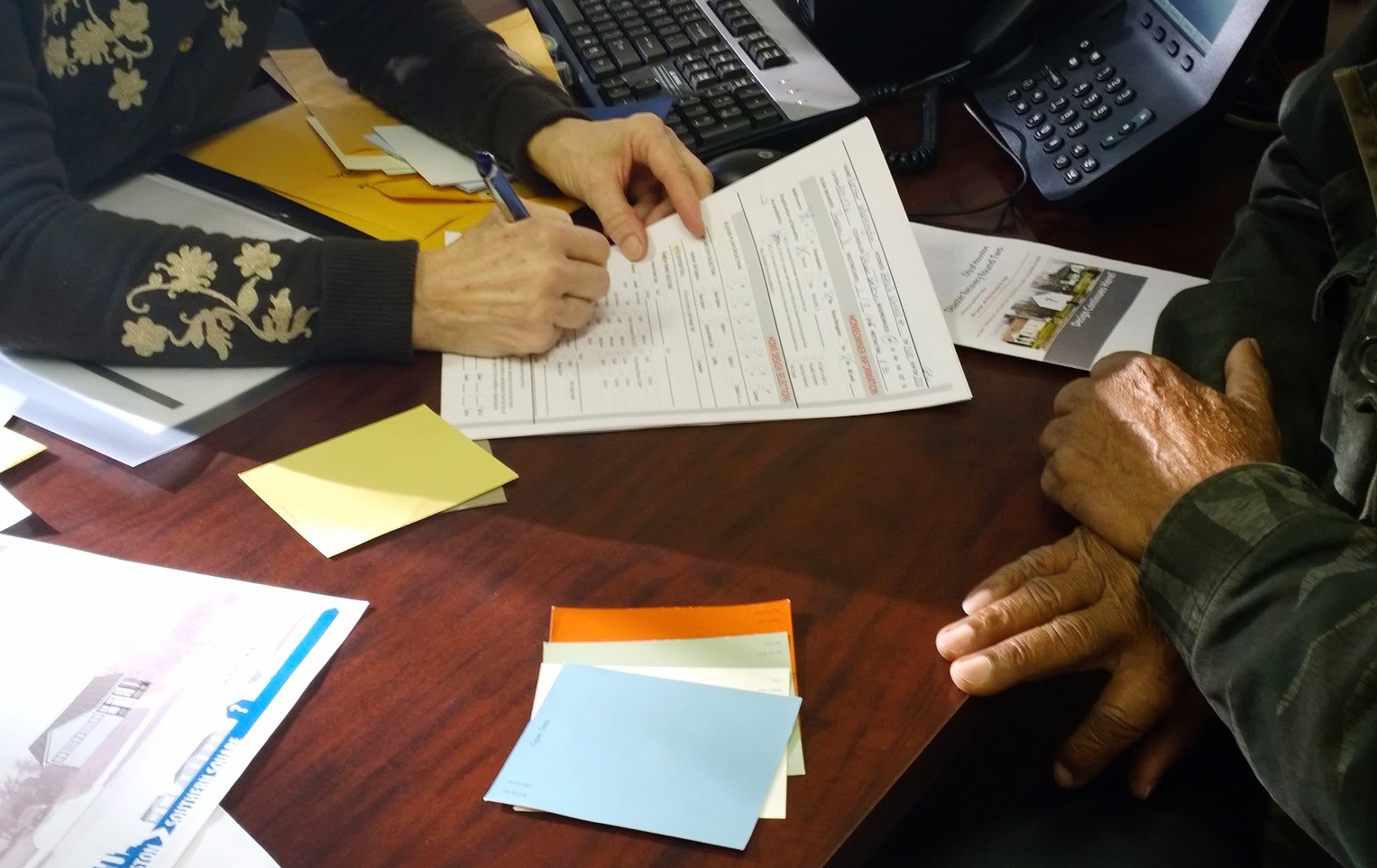

![[bc] staff and RAPIDO partners in the Rio Grande Valley help put together the DRH guide.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5248ebd5e4b0240948a6ceff/1424298638265-L96O7YQDA7NH29NRHNF4/P1000985.JPG)

![[bc] team building the floating platform, using lumber and repurposed palettes.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5248ebd5e4b0240948a6ceff/1419004388042-H4F9NTQ5Y4LNU9BX28TG/1.jpg)