Dallas neighborhood names speak volumes about the city’s complexion. Just as our words offer insight into our character, the way the city describes itself and names its parts- its toponymy- offer insight into its anatomy, its aspirations, its values, and its history. Rather than a study of the origin of individual place names, this is a typology of toponymy, revealing the city’s values through categories of place names. Neighborhoods are the building blocks of cities; what information can we elicit about the city collectively from the kind of names it gives it components?

Read More[bc] and Downtown Dallas 360

Over the past two months, [bc] has participated in six public events for Downtown Dallas 360, the recently revisited master planning process undertaken by the member-based Downtown advocacy organization Downtown Dallas, Inc (DDI) and its project partners. [bc] is among those partners, teaming up with DDI to incorporate Draw Your Neighborhood into the 360 engagement process.

Read MoreData Social Hour

Learn more about bcANALYTICS.

Join us Thursday, November 12th from 6:30-7:30pm for a meet and greet with members of the local data community. Meet others interested in leveraging data to make meaningful changes in our communities and neighborhoods!

Appetizers and drinks will be provided.

CLICK HERE TO RSVP

Geography of Food Security

Learn more about bcANALYTICS

[Note: The data and report presented here are for informational purposes only. This report does not represent the current strategy and operations of CCS.]

Crossroads Community Services (CCS) works to ensure that all people in Dallas County have ready access to nourishing foods and to provide life-skills education to help reduce obesity in impoverished areas. To help serve those in need, CCS participated in the 2013 - 2014 class of the Data Driven Decision-Making (D3) Institute hosted by the Communities Foundation of Texas (CFT). The D3 Institute works to give organizations the skills and tools necessary to incorporate data into their work serving low-income working families.

Following their participation in the D3 Institute, D3 participants were eligible to submit letters of interest to receive an analytics package from bcANALYTICS sponsored by CFT. In their LOI, CCS sought to identify small areas of Dallas County most at risk of food insecurity for possible expansion of their network of Community Distribution Partners (CDPs). bcANALYTICS staff worked with CCS to refine the research needs into a data driven, actionable research question and a work plan to answer the question in three months.

The three month project was split between four main phases – Connect, Discover, Analyze, and Deliver -- in order to perform a literature review, data collection, analysis, and compilation of a final report sharing contextual information and recommendations for CCS’s expansion strategy. This project required a considerable amount of background research on food deserts, food insecurity, and CCS’ client base in order to understand the myriad issues relating to the food landscape in Dallas County.

Ultimately, the report produced estimates of food insecurity at the Census Tract level and used geospatial techniques to identify areas underserved by grocery stores and food pantries. The intersection of food insecurity and food deserts was the starting point in identifying specific neighborhoods in Dallas County where CCS could focus on expanding the CDP network. Five neighborhoods were selected and explored at a more fine-grained level: the Los Encinos and Westhaven neighborhoods in far west Dallas; and parts of Pleasant Grove, Pleasant Mound, and Pemberton Hills in southeast Dallas.

Selected findings from the report:

- 34% of food distributed by CCS to CDP sites flows to southeastern Dallas County.

- Children under 19 make up 31% of the overall population in Dallas County, but this same age group makes up 46% of CCS clients between 2012 and 2014.

- Roughly ¼ of the food insecure population in Dallas County, 133,00 people, live in areas of concentrated food insecurity (Census Tracts with food insecurity rates greater than or equal to 20%).

- Much of Dallas County’s food insecure population live in areas that have low accessibility to grocery stores and food pantries.

Rapido wins SXSW Eco Place by Design Award

Learn more about RAPIDO and other SXSW Eco award winning projects.

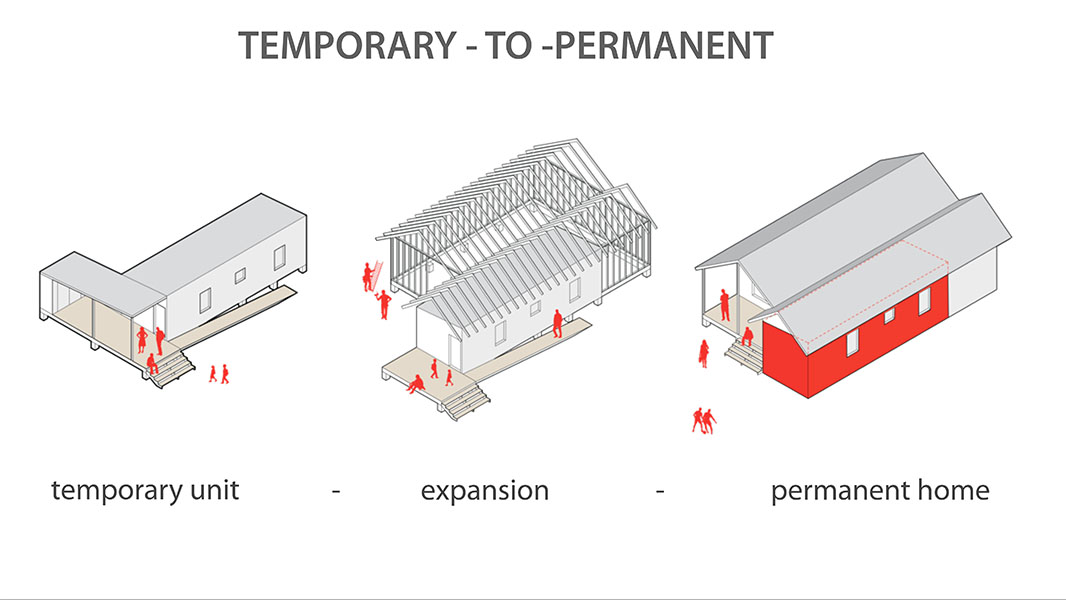

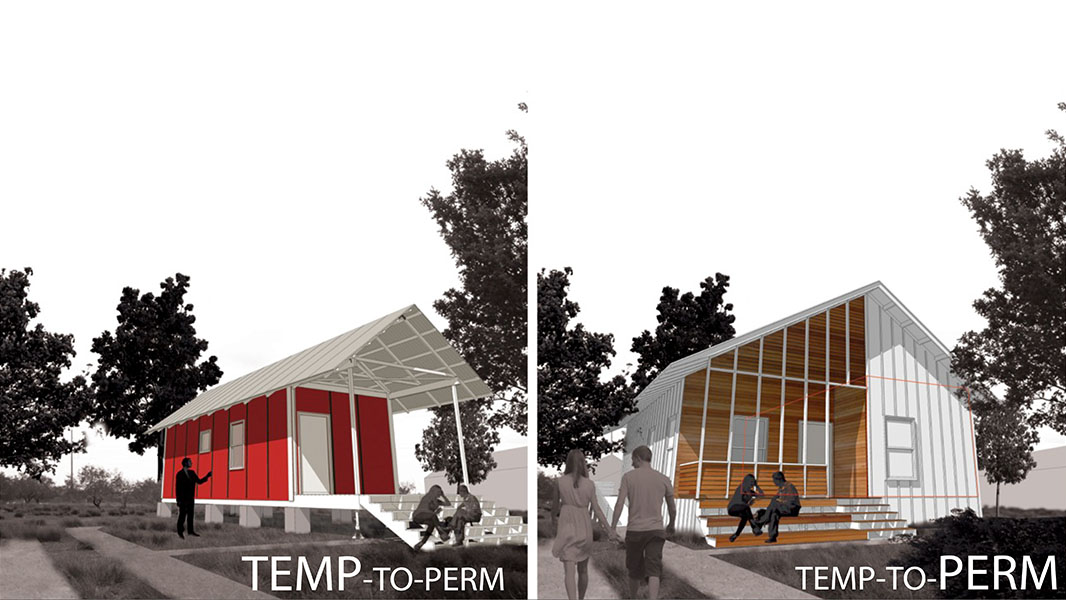

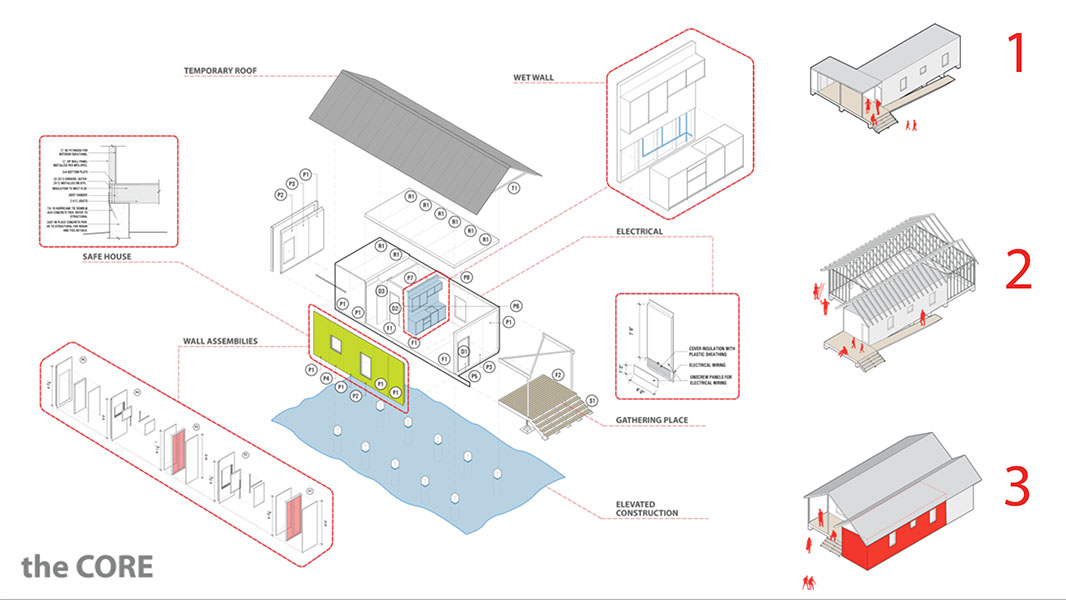

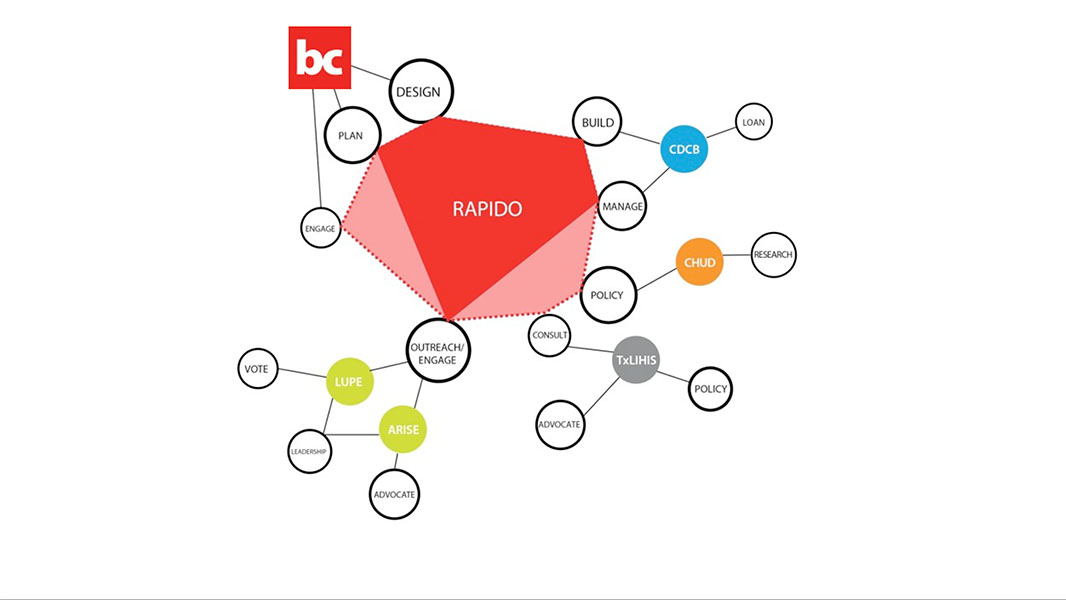

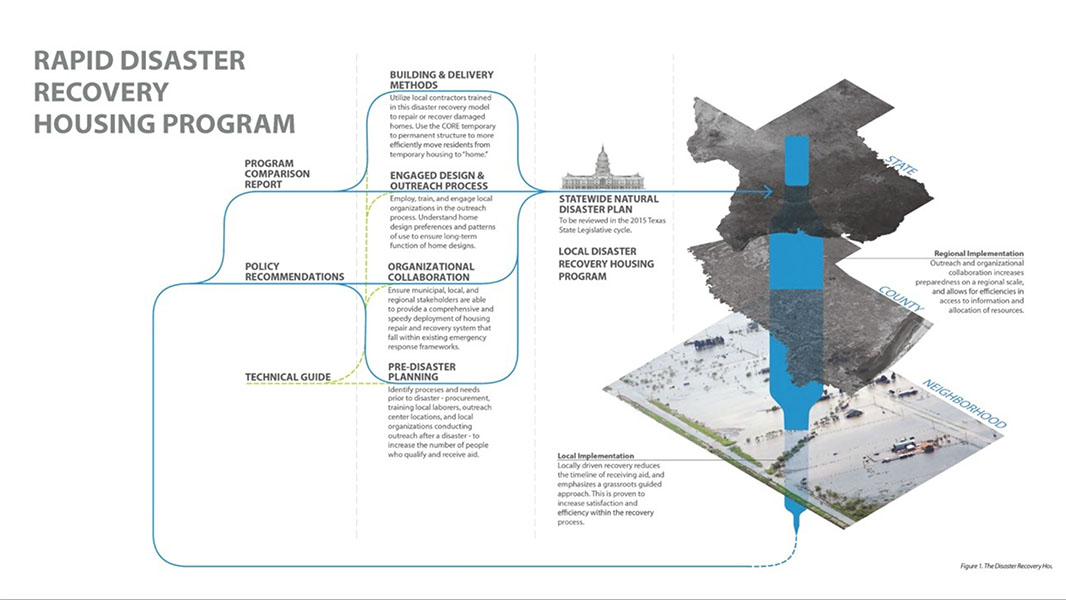

We are very excited to have presented RAPIDO, our disaster recovery housing pilot program, at the SXSW Eco 2015 conference this past Monday, and we are very honored to have been awarded 1st place in the Social Impact category of the Place by Design Competition.

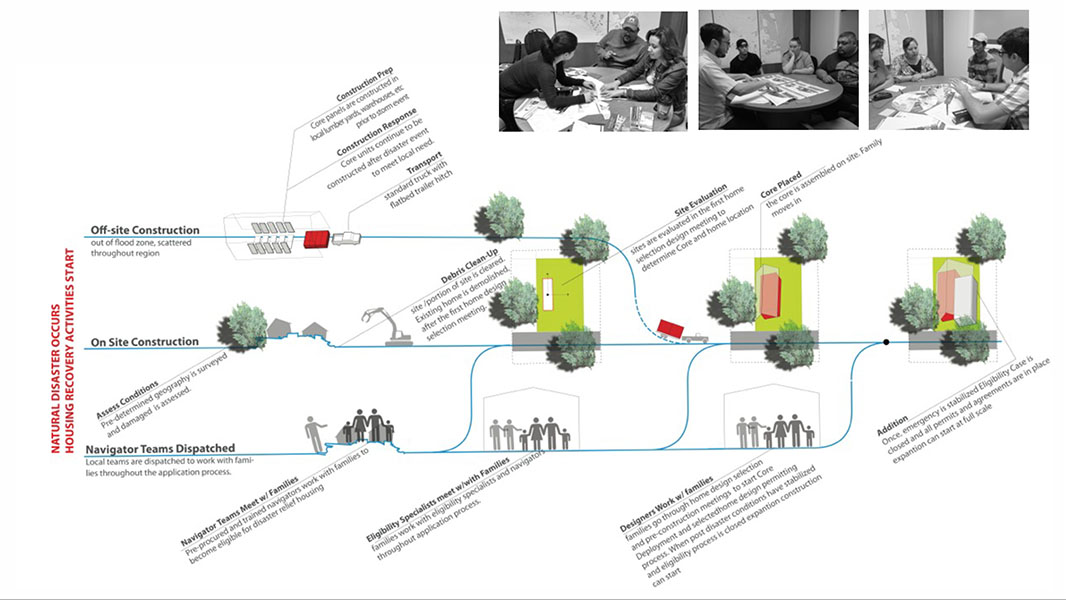

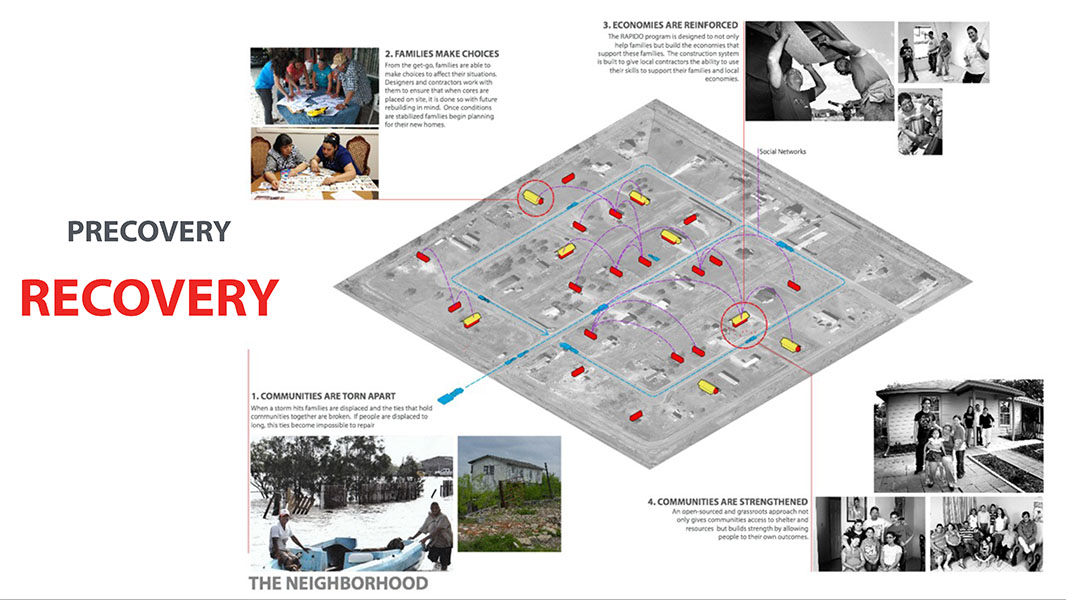

[bc]‘s Elaine Morales shared how the work of RAPIDO has created a great impact in the Rio Grande Valley, and how it can be implemented as a holistic approach to disaster recovery in other communities. The RAPIDO team designed and built 21 prototype homes with families affected by Hurricane Dolly in 2008, as well as designing a comprehensive system that empowers local teams to better prepare, respond and recover from natural disasters without sacrificing home design and quality. The audience feedback to our work was amazing and we were thrilled to have been part of the event and share experiences with entrepreneurs, designers and the general public on how to better serve the places we live in and work with.

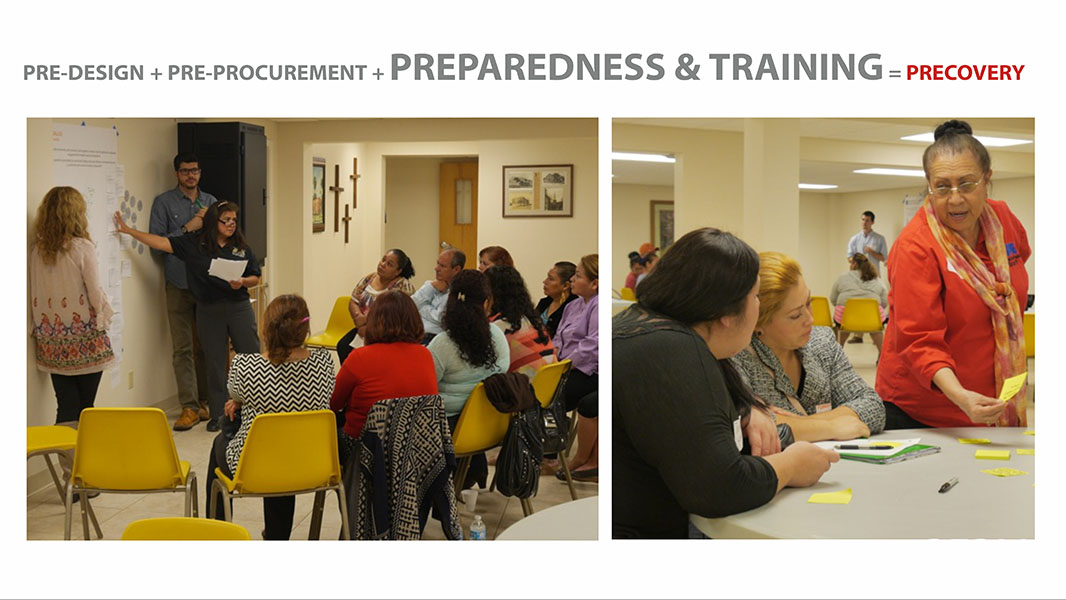

“The Rapido model starts recovery activities prior to a disaster. We call it precovery. Precovery means pre-designing to increase the variety and quality of home designs available, pre-procurement to allow housing recovery to start at the earliest, and preparedness and training to build reliable teams that support local jurisdictions and assist families through the recovery phase. By investing in precovery activities communities will be better prepared to recover.” - [RAPIDO Place by Design Competition pitch]

The SXSW Eco 2015 Place by Design Competition validated the need of changing the culture of design practice and academia by implementing an experience based learning approach within the design process through listening to what communities have to say, learning to ask the right questions, and measuring impact.

You can see all of the award finalists here and learn about some great place making efforts from around the world.

POP at the DHL Boot Camp!

Two weeks ago, as part of our year long POP Neighborhood Map engagement process, [bc] participated in the annual Dallas Homeowners League (DHL) Boot Camp. This years DHL gathering, titled "Return of the City", brought together neighborhood leaders from across Dallas for a day of discussions and best practice-sharing.

Read MoreThe History of the POP Neighborhood Map

[bc] has always aspired to impact neighborhoods across the state by using design to build capacity and empower communities. In Dallas, [bc] reasoned that in order to support neighborhoods through our work, we first needed to know what and where the neighborhoods of Dallas were, launching what was then known as the Dallas Neighborhoods Project.

Read MoreIntroducing the POP Neighborhood Map blog!

The POP Neighborhood Map Blog is a new digital platform that will chronicle the evolution of the POP Neighborhood Map and expounds why neighborhoods matter. The launch of this blog coincides with the launch of two new interactive digital tools - Know Your Neighborhood and Draw Your Neighborhood - the most recent effort of our ongoing POP Neighborhood Map project.

Read MoreBelden Connect: Beyond the Belden Trail

Learn more about the Belden Trail here.

Belden Connect is an extension of the existing mile-long Belden Trail that will run from Palm Boulevard and connect to 6th Street in downtown Brownsville. With funding from the City of Brownsville, it will reactivate another stretch of the abandoned railroad easement before turning onto Old Alice Road, where there will be a dedicated bike and pedestrian lane that is safely separated from vehicular traffic. The amenities from the existing trail, which range from custom benches, trash cans, native vegetation and pavilions will continue onto the extension. The connection to downtown will link the Belden Trail to the Mitte Cultural District and the Historic Battlefield Trail.

On Monday, May 18, [bc] organized the first community meeting with residents and business owners adjacent to the proposed trail extension. At the meeting, neighbors and business owners voiced their opinion on the location of the trail, the type of program they wanted, and other design priorities. We learned that the group was very excited about a potential outdoor dining area behind the local restaurants on the trail and have incorporated space for that to happen in the future. They also preferred to have the trail moving away from the backyards of residents, leaving space for new wildflowers, grasses and trees.

On May 28, [bc] held a second community meeting regarding the design of the new trail extension. The meeting took place at the Pavilion, located at the end of the Belden Trail, so attendees could reflect on what they liked about the current trail. Attendees then walked down the proposed trail path to give their feedback. We coordinated the event with a bike ride organized by the Brownsville Bike Brigade and invited local wellness groups, recreational advocacy groups and bike enthusiasts. Approximately 30 - 40 community members participated in the meeting.

The May 28 event kicked off with an exercise to understand what people liked and disliked about the existing Belden Trail and other trails in the area. We learned that people love the smooth pavement, easy access and social aspect of the trail -- however, they also want more connections to major sites around town, more shade and better methods for dealing with graffiti and litter.

The project proposes extending the Belden Trail towards 6th St in Downtown Brownsville to connect to the Mitte Cultural District, museums, and the exiting Historic Battlefield Trail.

The community prioritized the pavilion, bench locations and bike racks. The group also voted on vegetation types and tree species, showing a strong preference for wildflowers and native grasses over mown grass. We also solicited ideas on how we could use the old railroad infrastructure as the base of a public art piece that serves to beautify while also slowing vehicle traffic. The group cited murals, placemaking signage, interactive lights to calm traffic and several other great ideas.

The project will run along an abandoned railroad right of way behind Palm Village Mall and Old Alice Rd. The first segment will be similar to the existing Belden Trail, while the second segment will be a designated pedestrian-bike lane connecting to 6th St.

Public Design Impact Initiative: 2015 Project Selections

Learn more about the Public Design Impact Initiative.

Pictured Above: The first community meeting for the Forest Hills Neighborhood Association PDII project to design a comprehensive landscape plan for the medians of three boulevards in their neighborhood.

In February 2015 an Request For Proposals was released to invite Dallas/Fort Worth nonprofit organizations and groups to submit project proposals to be matched with pro bono design services. From this RFP, we received many excellent proposals, and in March, a jury of nonprofit, community and design leaders convened to review and provide recommended the following project selections for 2015.

2015 PROJECT SELECTIONS

Feed by Grace

Feed by Grace (FBG) operates Unity Park, providing Fort Worth’s homeless a safe haven from the drug dealers and violence of the street. Recently, donors have gifted structures to serve as a classroom and community building in the park, an outdoor pavilion, and outdoor signage. Naturally, we are excited about these gifts, but they have presented some unexpected challenges.

In this project, FBG envisions professionals: a) analyzing the park site, the footprints of proposed classroom, pavilion, and community buildings, other hardscape (signage, flagpole, picnic tables) and the general traffic flow in the park, b) recommending best placement for the proposed structures, c) presenting solutions to accessibility concerns that will be cost-conscious while in compliance with the city’s permitting requirements, d) presenting solutions to assure a safe and pleasant outdoor environment around the structures, and e) designing attractive yet hardy landscaping.

FBG envisions this grant providing professional help in creating solutions to accessibility through a porch, ramps, or other inventive means. FBG would also like assistance in landscape design to assure a pleasant outdoor environment around the proposed buildings and accessibility features. Through the grant, these services would assure our disabled neighbors could easily participate in courses and services meant to help them transition back into the larger community. The landscaping will improve the park’s aesthetics and further develop positive relationships with local businesses.

Forest Hills Neighborhood Association

Initiate an urban forest approach to maintaining and improving the medians in the Forest Hills neighborhood. The objectives are to ensure that the right trees are planted [currently and in the future]; in the right space and in the right way. The medians in our three boulevards [San Rafael, Forest Hills & Breezewood] have a total of 20 unique parcels with a variety of trees and shrubs.

According to the U.S. Forestry Service: “Urban forests, through planned connections of green space, form the green infrastructure system on which communities depend. Green infrastructure works at multiple scales from neighborhood to the metro area up to the regional landscape.” As dynamic ecosystems, urban forests help clean the air, add economic value and connect people to nature. Our goal, as next door neighbors to White Rock Lake and Park and the Dallas Arboretum, is to be good stewards of our urban natural resource through the maintenance and improvements to our medians.

Old East Dallas Association of Neighborhoods

Plans for alternative infill townhouses for the typical residential lots (50’ by 140/150’) located near the Old East Dallas historic districts, in neighborhoods that were formerly single-daily and now are zoned MF-2. The current development model maximizes paved areas with limited to no permeable surfaces or landscaped areas. This typically replaces a small house surrounded by permeable lawn and landscape. Infill housing is needed to preserve economic diversity and affordability within the community.

The current development trends have greatly increased impermeable surfaces, and this has increased stormwater runoff contributing to flooding issues. Although the City is currently increasing storm piping to accommodate increased density in the area, this issue will only grow more severe as development density continues. Some existing housing lots are now listed within a flood plain, and this requires purchase of expensive flood insurance every year. Our goal is to provide a model that addresses increased storm water and also creates a more sustainable development model integrated with the streetscape and surrounding historic development patterns, including diversity of housing types and affordability.

Engaging the Homeless Community in Downtown Dallas

Learn more about our work in Dallas.

A video produced by [bc] Media Associate Craig Weflen highlights the Dallas Public Library's Homeless Engagement efforts.

On May 11, the Dallas Public Library asked attendees at a community forum on homeless engagement to reconsider their definition of community. Who are downtown Dallas' community members?

When asked to provide a strategy for building community between the homeless and the housed in Dallas, [bc] Founding Director Brent Brown added a similar sentiment: "Say 'hi' to people, and mean it."

When an everyday office worker walks down the streets of downtown Dallas, do they consider the homeless one of them? For the Dallas Public Library, the answer is clear: homeless people, as much as any other patron, are full community members in downtown Dallas.

Moderated by StreetView podcast host Rashad Dickerson, various community organizations discussed the role of the homeless in downtown Dallas during the forum and how to engage the homeless population through social services, the built environment and art. Panelists included the Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance, Willie Baronet of WE ARE ALL HOMELESS, and [bc] Founding Director Brent Brown.

"The physicality [of the city] is driven by economic considerations first rather than human considerations," said Brown.

Brown cited the lack of public toilets in downtown Dallas and the interactions that local homeless community members have with the [bc] office in downtown Dallas as examples of how the homeless community negotiates this physicality, while acknowledging the need for more comprehensive social services as well as the role of the Dallas Public Library in engaging the city's homeless.

The Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance provided a strategic plan for further engaging homeless populations in Dallas and significantly reducing homelessness. Another highlight of the panel included an activity by artist Willie Baronet in which participants were asked to hold up signs created by homeless people around the country and imagine their lives: Were they old or young? Were they men or women? Why did they choose to own a pet, if it was referenced on the sign? These questions sparked lively dialogue about community perceptions of the homeless in multiple contexts. Baronet also emphasized the importance of respecting a homeless person's humanity by physically acknowledging their presence.

Other ways that [bc] has previously engaged with the Dallas homeless community include the 5750 art installations and the making of a permanent supportive housing community known as the Cottages as Hickory Crossing.

To learn more about the Dallas Public Library's Homeless Engagement efforts, watch the [bc]-produced video above.

Q&A with John Henneberger of Texas Low-Income Housing Information Service

Learn more about our work in the Rio Grande Valley. Learn more about bcHEROES.

John Henneberger. co-director of Texas Low-Income Housing Information Service.

As a partner on the RAPIDO disaster recovery housing pilot project, Texas Low-Income Housing Information Service (TxLiHS) has been key in pioneering the principles of environmental justice, fair housing and equitable access to economic resources for all Texans. TxLiHS co-director John Henneberger, a 2014 MacArthur Fellow, emphasized these social justice principles during his speech at this year's University of Texas School of Architecture commencement ceremony. [bc] had an in-depth conversation with Hennenberger about his speech, his desire to advance the principles of social justice, and the relationship that architects, planners and designers have with social justice principles. (This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.)

Read Henneberger's commencement speech here.

[bc]: In your speech, you reference the image of John Wayne playing Davy Crockett in "The Alamo." You said, "Davy is explaining to his romantic interest why he is choosing to abandon her to stay and fight, and surely die with the defenders of the Alamo." Except for the dying part, when have you had to abandon something very important to you to do what's right?

[bc]'s Hugo Colón discusses stormwater drainage plans with a colonia community.

JH: I’m an impatient guy, and I come up with a lot of ideas for fixing things. I look at injustice, a disinvested neighborhood or an unmet housing need, and I see lots of possible solutions. My natural inclination is to rush off and push for a solution that seems immediately obvious to me. Sometimes it works, but oftentimes, in the end, it just misses the mark.

I wish someone had sat me down in 1975 when I was starting out and told me that I should never abandon this approach. I wish someone had told me then to always step back and make sure I really understood the underlying problem before proposing a solution. I need to be constantly reminded to stand behind good, honest community resident leaders who live with the problem, help them to see the full scope of the issue and not let my ego jump out in front of them.

This approach takes longer. It's more work. It's often frustrating. But digging deep into the real, underlying problems, aside those who are impacted by those problems, is the only way to uncover the real solution.

One thing I abandoned was running neighborhood community development corporations (CDCs). I ran CDCs for many years. I loved the work and the community residents I worked for. It was central to who I was. But, after a while, I came to feel that building another house in a low-income neighborhood was somehow not enough of an answer to the oppressive problems of race and class that were holding back the children of good people.

I had to step out of that housing production role to appreciate what building a house does and does not do to improve people’s lives. Don’t misinterpret this. I think CDCs are a vital part of the solution. But, it is hard when you are fighting for funding and dealing with architects and contractors all day to appreciate the serious problems of race and class that cannot be addressed solely by building a nice house in a distressed environment.

[bc]: You also mention that a design solution isn't enough to address problems of segregation and affordable housing. What is your philosophy about community building to get at those "underlying problems before you begin design.”

[bc]'s Elaine Morales discusses assembly of the CORE with construction workers during the RAPIDO project.

JH: First and foremost, we have to avoid building on a foundation of injustice. Jim Crow segregation created existing residential patterns. We must stop reenforcing those patterns and stop accepting racial and economic segregation.

It is not acceptable to confine more generations of children to concentrated poverty, environmental blight, failed schools and high crime. We have to accept responsibility for our roles as planners, architects, community development corporations, government officials and citizens by confronting the extent and depth of this problem of distressed neighborhoods and concentrated poverty.

When we participate in housing development that continues to stack poor families into these communities, no matter if it is a cool design, what level of LEED certification it earns, or what local political leader has championed it, we are as guilty of practicing discrimination as the folks in our positions were in the 1950s.

We will never transform distressed communities into good places to live simply by providing more and better subsidized housing there. It will take real commitment to comprehensively address public infrastructure, environmental hazards, public safety, employment opportunities and crime. It’s easy to throw up more affordable housing in distressed communities, but it is wrong for the people who live there.

Similarly, when we push poor families of color out of a historic neighborhood that is in the process of transitioning to a high opportunity, desirable place to live, we are engaged in an act of racial discrimination.

We have to stop acting like we are doing something good and noble when we build on apartheid and segregation. As leaders in affordable housing and community revitalization, we have to confront existing patterns and practices and demand justice. This is a social responsibility of design and planning that we have to accept.

[bc]: What is the role of partners in your work?

Juanita Valdez-Cox, a bcHERO.

JH: We want to see problems solved. The people who have to lead in that are the people who live with the problem. So, we stand behind grassroots community leaders and provide them with information, help them discover options for solutions, and find other forms of help, like architects, planners and CDCs to implement the solutions.

The work we are involved with in the Lower Rio Grande Valley is a good example. Low-income colonia residents first come together through community organizing groups to frame the agenda for change. [bc] helps assess the causes of the problems identified by colonia residents and finds solutions in areas like drainage and home design. Local CDCs like the Community Development Corporation of Brownsville put the solutions on the ground. The role of my organization is to understand and assess the policies that have produced the problem and to help colonia residents get their hands on the levers of power to change those policies.

[bc]: You told us about several of the important influences in your life in your speech. Who else would you add to that list if you could?

JH: My heroes are people who solve problems for people who are poor and oppressed. The people who most influenced my life are a number of very wise and brave African-American and Hispanic neighborhood leaders who stand up to the power of the government, powerful wealthy interests and general public apathy to demand justice on behalf of their families and their neighbors. For the most part, these are women who are not well known outside the community where they live and work.

The neighborhood center director in the freedman’s community of Clarksville in Austin was my first mentor. Ora Lee Nobles, a neighborhood leader in East Austin who fought against urban renewal in the 1970s and 1980s, is another. Others include Sister Amalia Rios, who helped found an early Texas community development corporation, Juanita Valdez-Cox, and Lourdes Flores, who lead the fight for basic public services for immigrants and other poor Texas families living in colonias. I can name about a hundred folks like these who are unsung heroes.

[bc]: You've been very busy the past few years on the disaster recovery housing front. What else needs to happen there? Anything new on your horizon that you're focusing on?

JH: Local communities need to plan in advance of a disaster for how they will help people rebuild their homes, especially poor people, the elderly, people living with disabilities and working class folks. Local citizens need to look at their communities and ask themselves, “What kind of community to we want to be? Do we want to rebuild what we have, or do we want to rebuild an inclusive, safe, diverse community?"

Once we decide that, then city officials, neighborhood leaders, planners, builders and other stakeholders need to decide how to get there. That will mean planning before disaster strikes so we have time to think the process through and get it right. It also means cities working cooperatively with the State of Texas, HUD and FEMA to create a plan that everyone can support to implement a local vision. That is what the RAPIDO pilot program that [bc], the Community Development Corporation of Brownsville, Texas A&M and community groups in the Lower Rio Grande Valley have shown is possible.

We are also working on issues of neighborhood inequality with organized grassroots groups in the Valley, Houston, San Antonio, Austin and Dallas. It is really the same work we have been doing for the past forty years. But, we are always learning and thrilled and inspired by discovering new local grassroots community leaders who are committed to speaking up for what’s right.

Elotes, Raspados and Urban Planning in the Rio Grande Valley

Learn more about our work in the Rio Grande Valley.

Elotes, raspados and tacos are just some of the many popular Mexican street foods that form a large part of street life and urban culture in areas along the U.S.-Mexico border, including the Rio Grande Valley. In spite of their enormous popularity, mobile vendors selling those items often operate through the gaps of vague regulations in areas like Brownsville, where food trucks and food trailers are not allowed. Most mobile food vendors in Brownsville operate primarily during special events, such as Charro Days or at the local flea market.

[bc] and the City of Brownsville teamed up for a community outreach workshop on May 6 to discuss the possibility of adjusting codes and ordinances to regulate mobile food vending units and explore the possibility of a food truck park pilot in Brownsville as part of the programming of the Brownsville City Design Studio. During the workshop, Brownsville Redevelopment Director Ramiro Gonzalez gave an overview of the current situation regarding the city's mobile food vendors as well as ideas on how to regulate mobile food vending. Many cities have incorporated food truck parks into their city planning with great success: Austin and McAllen are two prominent examples that were showcased at the May 6 workshop.

Attendees provided creative ideas to incorporate food trucks to Brownsville’s landscape. One workshop attendee suggested allowing mobile food vendors to operate in existing city parks or vacant land instead of creating new space for them. Others suggested placing food trucks in areas that needed food vibrancy, like the Mitte Cultural District. Though most attendees were in favor of the creation of one or multiple food truck parks, there were a small number of particularly vocal opponents: these opponents were concerned that the mobile food vendors were "unsanitary" and not subject to the same regulations as standard food businesses.

However, according to [bc] advocate Elaine Morales, the disagreement over the cleanliness of mobile food vendors in the RGV is also linked to another principle: aesthetics.

In the past, mobile food vendors added multiple attachments to their units or removed the wheels from their units In their quest to comply with local regulations that in many cases were created for brick and mortar restaurants. For example, a vendor who sells raspados, a type of snow cone, will often add a sink to the side of their cart in order to comply with a city rule that requires all food vendors to have access to a hand washing sink. In spite of this, workshop attendees and local food business owners expressed sanitary concerns about mobile food vendors handling money with the same hands that they used to handle food.

Cultural norms around what a food vendor is also differ significantly between geographies - the mobile food vendor units that currently exist in the RGV differ considerably from what many citizens see in cities like Austin: brightly-lit, large food truck parks with trash cans, benches and tables for patrons. Substandard units in the RGV have affected the perception of what mobile vending units can be.

"One of the opponents to food trucks at the community workshop had admitted that she had never been to a food truck park,” said Morales.

The conversation about food trucks in Brownsville will continue with the creation of a committee or task force involving both the city and its citizens. One city official from Austin, Marcel Elizondo, recalls that it took their city almost 19 months to finalize regulations for mobile food vendors.

More community-focused workshops in Brownsville beyond the topic of mobile food vendors are in the works for the next months.

The Second Annual Ark Festival: The History, Present & Future of Tenth Street

Learn more about Activating Vacancy.

Last year, as part of our Activating Vacancy initiative, artist Christopher Blay and [bc] collaborated with the Tenth Street Historic District community to produce the Ark on Noah Street. The Ark is a sculpture, a gallery, a museum and a symbol. When Christopher Blay created the concept of the Ark, a fundamental facet of the project was that it be reproduced yearly to keep art and culture active in the Tenth Street Historic District and to create an opportunity to celebrate, share and reflect on the neighborhood's history and the changes of the year.

On May 2, 2015, the Ark was again commemorated during the Second Annual Ark Festival, a gathering of the Dallas arts community and the Tenth Street Historic District that was even bigger and better than before! The festival featured a processional of residents with original artwork depicting the neighborhood's history and its growth since the Ark was last seen, a performance of the original Story Corners play "A Freeman Cries for the Future," a visit from the Dallas Zoo, and the return of the Neighborhood Stories: Tenth Street exhibit. There was also a small marketplace for neighbors and arts activities led by Oil and Cotton.

The Tenth Street Historic District is one of Dallas’ oldest neighborhoods and one of its few remaining freedmen’s towns, communities built by freed slaves following the Civil War. Despite being designated a landmark district by the City of Dallas in 1993 and being listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994, the neighborhood has lost population and housing stock at a rapid pace. It has also experienced a growth in crime and a deteriorating public image. In response to these challenges, [bc] initiated Activating Vacancy to encourage residents to reshape the vacancy in their neighborhood from blight to opportunity through a series of public art activities, beginning with the Ark on Noah Street.

Activating Vacancy existed at a nexus of creative placemaking, public art and community organizing. Inspired by similar initiatives such as the Heidelberg Project in Detroit and Project Row Houses in Houston, Activating Vacancy sought to set in motion the revitalization of an important historic community, provide commentary regarding an array of urban issues such as vacancy and historic preservation and encourage a democratization of exceptional art in Dallas in terms of audiences, geographies and producers. The Ark on Noah Street was an excellent first step towards achieving these goals. The Ark as a gallery featured artwork produced by neighborhood residents. The Ark as a sculpture artfully repurposed discarded materials from Tenth Street's historic homes into a monument and testament to its history. The Ark as a festival brought neighbors, artists, critics and art consumers together to meet each other, rediscover an often forgotten part of Dallas and imagine a city where any neighborhood can be recognized as a source of valuable cultural producers.

At the Second Annual Ark Festival, it was made clear that the Tenth Street Historic District still faces tremendous challenges. Homes have been repaired, while others have been demolished. Crime is tempered, but it persists. There is also evidence of renewed action in the neighborhood: dozens of attendees wore Operation Tenth Street t-shirts, representing a new, forward-thinking neighborhood organization that has secured grant funding for neighborhood improvement projects. The Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church has been repaired and again opens its doors to song and prayer on Sunday morning. And, the Ark has been rebuilt, fuller and more refined than its previous iteration.

In addition to the above challenges, there are a bevy of questions that have yet to be answered about the neighborhood that will help illuminate how sustainable its recent burst of energy is. Will Tenth Street be able to continue its revitalization with reduced non-profit activity? What will it take for Tenth Street to develop market interest in rebuilding its historic ground? Have recent efforts sufficiently demonstrated the neighborhood's value to the city at large to insist on its survival, whether through ongoing preservation efforts or through continued nurturing of its unique identity and role as cultural producer? Perhaps some of these questions will be answered and shared at the Third Ark Festival.

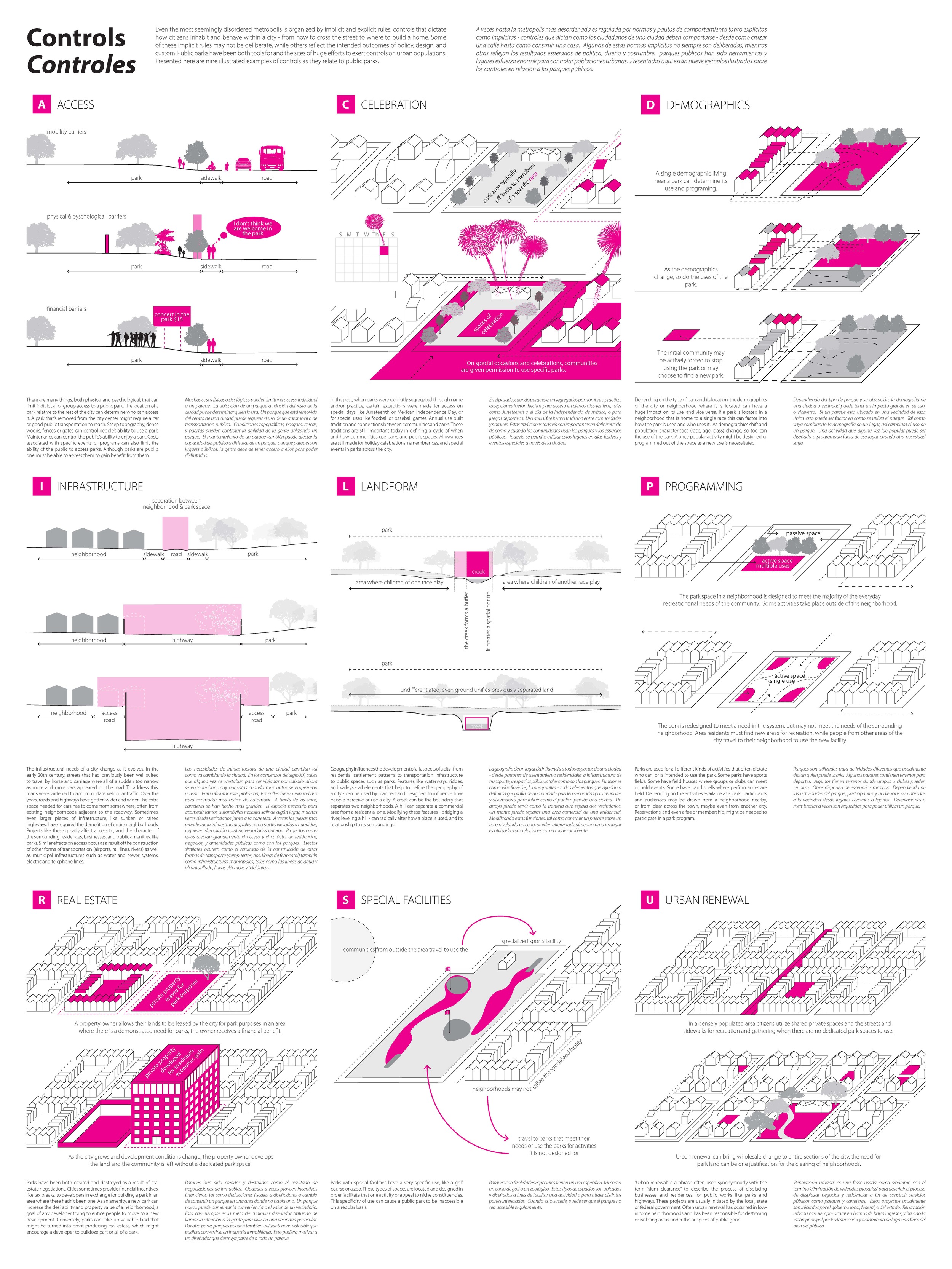

Texas ASLA Honor Award 2015: Race and the Control of Public Parks

Learn more about Race and the Control of Public Parks.

We're excited to announce our project on Race and the Control of Public Parks has received an Honor Award from the Texas chapter of the American Society of Landscape Architects!

According to the Texas ASLA, Professional Honor Awards are given to projects that highlight the diversity, distinction and ingenuity of landscape architecture. Race and the Control of Public Parks won in the research category, and the exhibit recognizes the ways in which the design, construction, programming, use, and alteration/renovation of public parks can reinforce divisions, both physical and perceived, between populations.

Community Design Lessons at Structures for Inclusion 2015

From April 11-12, [bc] presented at the Structures for Inclusion conference in Detroit, MI and learned from other examples of public interest design. Elaine Morales-Díaz contributed to the discussion on the role of resiliency in public interest design by presenting the disaster recovery housing program, a context-based, innovative model for disaster relief housing that encompasses all of the tenets of resiliency. Resiliency not only includes recovering from a disaster, but preparing for recovery in a comprehensive way (also known as "pre-covery") that allows local teams to respond & adapt to current or sudden adversities without sacrificing community engagement, home design, or home quality. Projects from Detroit and other resilient cities were presented to practitioners of public interest architecture & design, who were challenged to incorporate community engagement principles into questions of urban revitalization and resilience.

Structures for Inclusion is an annual conference hosted by Design Corps that features SEED Award winners. The SEED Award is given to design and architectural projects that have exceptional social, economic and environmental impact.

There were also lessons we took from the context of Detroit. The Impact Detroit Community Development Guides have resonance for [bc]'s three geographies given that they all face the challenge of dealing with vacant urban in-fill. The guides provide a way for citizens and community members to participate in revitalization and development efforts. Detroit's location also provided valuable takeaways on engaging people outside the design community in public interest design work. A solid methodology is key to engaging various stakeholders, as well as reflecting on what went well during the design process & what didn't. [bc]'s six core methods of work -- informing, analyzing, activating, mapping, making & storytelling -- are designed for that purpose. Understanding the relationship between design & other elements in the built environment requires seeking knowledge outside of our field.

In particular, the El Guadual Youth Development Center in Colombia is an example of how architecture can provide appropriate facilities for young children in an educational context while incorporating students into the design process. However, the buildings themselves were a catalyst for social improvement, and their design/construction programs increased the local community's skill set. In Brownsville, [bc] has developed a house design to be built by participants in the Youthbuild program, which aims to teach low-income youth construction skills in the Rio Grande Valley.

Susan Szenasy, editor-in-chief of Metropolis Magazine, was also a keynote speaker on Saturday night. She provided sharp insight on how architects can better engage stakeholders and communicate their intentions more clearly through the showcase of projects like Via Verde in New York City. Via Verde is an example of how affordable housing can be beautiful, low-cost, and provide dignity & choice to its residents. Projects where we strive to encompass these principles include Congo St. in Dallas and DR2 in Houston. DR2 in particular has incorporated housing choice among residents as a key component of the post-disaster housing recovery process. Szenasy also mentioned how Metropolis' relative lack of architectural jargon and commitment to storytelling makes design more accessible to the public. [bc] strives to make sure its informing & storytelling efforts are relevant to a wide range of audiences both inside and outside the design community through the use of web posts, social media, community engagement events, and neighborhood research.

Overall, SFI 15 was a positive experience, especially for the seven bcFELLOWS in attendance -- it provided networking opportunities and showcased examples of public interest design in a variety of contexts. The conference allowed fellows in particular the opportunity to engage with a variety of practitioners & observe different models for practicing public interest design.

PIDI Brownsville: Building Healthy and Resilient Environments

Learn more about our work in the RGV.

On January 30th & 31st, 2015, [bc] hosted the Public Interest Design Institute at the Market Square Center in Brownsville, TX.

The Public Interest Design Institute is a two-day course that provides design and planning professionals with in-depth study on methods of design that can address the critical issues faced by communities. The curriculum is formed around the Social Economic Environmental Design® metric, a set of standards that outline the process and principles of this growing approach to design. SEED goes beyond green design with a “triple bottom line” approach that includes social, economic and environmental issues in the design process.

PIDI Brownsville was the most highly-attended PIDI conference ever, thanks to Design Corps and to funders such as the Community Development Corporation of Brownsville (CDCB), Brownsville Community Improvement Corporation (BCIC), the LRGV chapter of the American Institute of Architects, the City of Brownsville, and [bc], who enabled free and low-cost attendance at the event.

PIDI Brownsville presented an array of topics focused on issues faced by most communities in the Rio Grande Valley, such as housing, infrastructure, downtown revitalization, and public health. Panelists discussed how to harness community partnerships and design for the public interest as a tool to improve our communities and build healthy and resilient environments. The diverse audience in attendance (city and county employees, local and international design professionals, engineers, [bc] partners, architecture students and community organizers) contributed to a productive discussion of these issues and possible solutions.

Speakers included Nick Mitchell-Bennett, Executive Director of CDCB, Maurice Cox, as well as Brent Brown and staff members from the [bc] Rio Grande Valley office. By contextualizing the principles of public interest design into the issues that Brownsville & the Lower Rio Grande Valley are facing, participants learned how to use public interest design when planning for diverse needs, such as infrastructure, public health and post-disaster recovery housing. Participants from Monterrey, Mexico also expressed their desire to apply practices from public interest design in the U.S. to issues being faced in their respective communities.

PIDI Brownsville events included:

Day 1:

[PANEL] Inclusive Strategies: Leadership and Partnerships

[PANEL] Building It Better: Resilient Housing and Infrastructure

[LECTURE] [bc]: Working Across Scales: La Hacienda Casitas, sustainABLEhouse, and RAPIDO

Day 2:

[Keynote] - Maurice Cox shared his work from Charlottesville and his work with Tulane University in New Orleans. His design, political, institutional, and educational experience serve to tie the panel topics with what is currently happening in Brownsville.

[PANEL] Downtown Economics: Urban Redevelopment and Revitalization

[PANEL] Healthy Environments: Designing and Building Healthy Communities

“I'm a civil engineer, so it's kind of hard to apply PID to installation of a sanitary sewer line, for example. However, I frequently work hand-in-hand with architectural firms (civil site design) so the course did give me some valuable insight into the big picture, i.e. what a versatile design team is capable of accomplishing for the common good of the community,” noted one participant.

Check out the #pidibrownsville hashtag for coverage of the event on Twitter, including lessons learned from PIDI Brownsville:

Invest in the people to reach sustainability goals.

Collaboration & teamwork is essential to serving the public.

Partnership & interdisciplinary goals are necessary for successful projects with public-interest goals.

[bc] hopes to recreate the success of PIDI Brownsville in Dallas, TX. Join us for PIDI Dallas in September 2015.

Sharing the Deepwood Story

Learn more about Neighborhood Stories, and visit the film's website.

It’s been an awesome few months for Out of Deepwood! Since the community sneak preview at the Trinity River Audubon Center in September, the film has played in several film festivals. On October 15, Out of Deepwood premiered to the general public as part of Dallas VideoFest 27, as part of a block of films hosted by the South Dallas Cultural Center, which included 50 Years, The New South Dallas, and Dawn. This was a great experience for us, giving us an opportunity to bring this story to a wider audience, while still focused on southern Dallas.

Following Dallas VideoFest, we released the film free online, and were excited to receive an Award of Merit from the Best Shorts Competition. Even more exciting, we had the opportunity to share this story across the nation in February, as we were accepted to the Big Sky Documentary Film Festival in Missoula, Montana, and the Big Muddy Film Festival at Southern Illinois University Carbondale.

DVDs of the film are currently for sale at the Trinity River Audubon Center for around $5. We are committed to providing this film for all who want to see it, so the DVDs are being sold at-cost for those who would like a physical copy of the film.

Currently, we are participating in the Audience Awards, an online film competition that awards prizes based on the votes that a film receives. Be sure to vote for us over the next few days, but also take the opportunity to view some of the other great work featured in the competition!

We look forward to continuing to share this story as an example of neighborhood activism leading to real, positive change.

What people are saying:

- "'Out of Deepwood' Powerfully Recounts Southeast Dallas Neighbors' Fight Against Massive Illegal Dump." - Sharon Grigsby, Dallas Morning News

- “If you watch one 23-minute documentary about a former illegal Dallas dump today, make it director Craig Weflen’s terrific Out of Deepwood." - Robert Wilonsky, Dallas Morning News

- “A solid look at a well-kept secret both beautiful and horrendous.” - Gary Dowell, Theater Jones

- “Invaluable perspective on the events, old and new, that have greatly impacted the city, south of downtown.” - Chris Mosley, D Magazine

Recruiting Dallas Designers

On March 13, a group of DFW-area designers, urban planners & architects gathered at our office to learn about [bc]'s various designer partnership opportunities. At the social, [bc] shared with attendees the upcoming projects that need design partners to get involved. Below is an overview of the short presentation given during the social as well as the accompanying slides.

Read MoreCall for Design Partners

[bc] has found that the partnerships between designers/architects and community-based organizations are mutually beneficial, building the knowledge and experience of both to better serve others. With that in mind, [bc] is inviting local design professionals to become Design Partners to provide their services to meet the needs of local nonprofit and community organizations. There are a variety of roles for designers, architects, landscape architects, engineers, graphic designers, and planners of all levels of experience.

Read More![[bc]](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5248ebd5e4b0240948a6ceff/1412268209242-TTW0GOFNZPDW9PV7QFXD/bcW_square+big.jpg?format=1000w)

![Elaine Morales of [bc] presents on the RAPIDO project using a resiliency framework.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5248ebd5e4b0240948a6ceff/1429540065586-GX750RGCCERH49KXHW55/SFI1+copy.jpg)